Open House New York provides broad audiences with unparalleled access to the extraordinary architecture of New York and to the people who help design, build, and preserve the city about how the city might take shape in the years ahead, and address issues including planning, preservation, infrastructure, and contemporary design.This year Estonian House was also part of the open house program.

It was not even 10am yet when people started gathering to get in to the house. All the rooms were open for the visitors, Estonian music was playing in all rooms and a historical movie was playing downstairs. Estonian House had three tours on Saturday sharing the Estonian House History and information about Estonia. Over 900 people were visiting the Estonian house that weekend, many of them passing the house every day and always eager to see how it looks and what is going on inside. Amest Foods was passing out free Estonian dark rye bread and first tour was treated to a free shot of Vana Tallinn. Tour guides were Estonian Educational Society president Dr. Toomas Sõrra, board member Carl Skonberg and business manager Kadri Sepp.

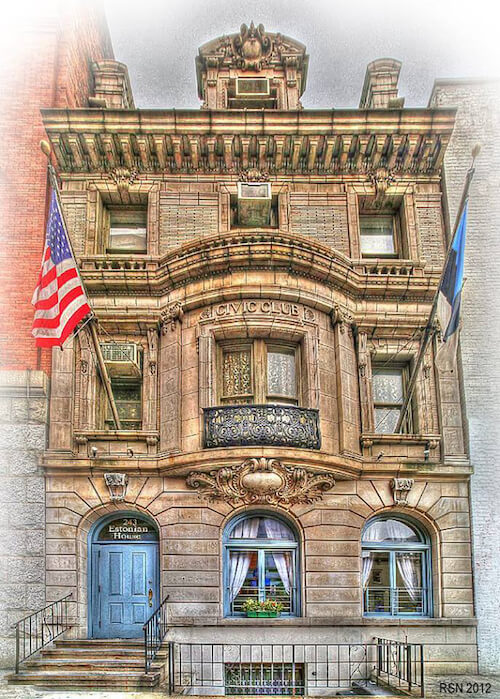

Unselfish Wealth – The 1899 Civic Club – 243 East 34th Street

Frederick Norton Goddard was not like his peers in the glittering, gilded social circles of New York in the 1890s. When Goddard’s father, J. W. Goddard died he left an estate of approximately $12 million to be divided between his two sons. F. Norton Goddard found himself less interested in Madison Avenue gentlemen’s clubs and chandelier-lit ballrooms than in the condition of the impoverished working class.

Shortly after his father’s death, he left his mansion with one old and trusted servant “in search of men nearer to nature than his former friends.” Goddard rented a floor in a tenement building at 327 E. 33rd Street and took up the life of a working man. Later he would admit that he did so not with any particular idea of doing good or helping other men. His desire was “to escape a life that had become irksome.” It was a decision that would change his life and that of thousands of New Yorkers. Years later The New York Times would comment “And he did not go among them to study them, to use them, or to pity them. He lived among them as one of their own, sharing their cares and pleasures, sorrows and confidences.”

In 1895 Goddard ran into a group of blue collar workers – a bricklayer, a plasterer , a ferryboat worker, for instance – who had decided they could improve their lots by improving the conditions of others. He asked to join their “club” and before long was its leading force. The Civic Club, as it came to be known, started out rendering personal service and financial aid to anyone needing it within the district between 23rd and 42nd Streets from Park Avenue to the East River. Before long he had convinced other wealthy businessmen like P. Tecumseh Sherman and John H. Hammond to contribute to the causes of The Civic Club, including bad sanitary conditions, bad plumbing, dangerous sidewalks, policy swindles (a numbers-type gambling racket that preyed on the poor) and other problems. In 1898 he commissioned Brooklyn architect Thomas A. Gray to design a permanent clubhouse at 243 E. 34th Street. A year later the Civic Club was completed, paid for in full by F. Norton Goddard.

Ironically, the French Beaux Arts building was similar to the grand limestone mansions Goddard had fled. The rusticated first floor with two arched windows and a matching arched doorway supports the second floor with a bowed central window with French doors and wrought iron balcony. The third story is gray brick, above which a handsome stone balustrade protects a steep mansard roof with a dormer. In 1899, the same year the building was completed, Goddard married Alice S. Winthrop and, necessarily, moved to a more substantial home at 273 Lexington Avenue. The Civic Club and his political activities with the Republican Party, however, never faltered. Annually, Goddard would host a ferry boat excursion for residents of the area. In 1898 7500 tickets were distributed which entitled the holder to a pint of sterilized milk, ice cream and a bag of fruit. “The excursion was not for the exclusive benefit of sick babies and children, but a social outing to make the Twenty-first Warders and the Civic Club better acquainted,” said The New York Times. “At the same time there was quite a number of sick babies, and yesterday’s outing probably saved the lives of several who might easily have succumbed to the depressing humid heat in the city.” By 1900 the number of participants had doubled to 14,000 women and children. Brass bands played on the barges that transported the throngs to the picnic grounds at Grand View Grove. “Capt. Goddard did not give any cake this year, because too many boys used it for missiles on his former excursions; but there were 7,000 quarts of the very best milk that the market affords and 2,500 quarts of ice cream in bricks wrapped in paper, and everyone on board had coupons calling for a fair share of both,” said The Times. On that excursion, one man foolishly ignored Goddard’s passionate hatred for gambling and set up a wheel of fortune at the picnic grounds. When a New York policeman accompanying the trip ordered the man to pack up his wheel, the cop was firmly informed that he had no jurisdiction this far from the City.

The New York Times reported on the reaction of a small child who saw the consequences of that comment. “’Oh, mamma! What a smash in the jaw!’ Yelled a delighted youngster who saw it. ‘Say, where did that geezer come from, to t’ink he could fight a New York cop?’” Although Goddard may not have approved of such physical contact, his campaign against street gambling, especially “policy shops” was perhaps his greatest obsession.

By 1901 the Civic Club had a defined organization. The Committee on Streets worked to keep the streets in “fair condition;” the Committee on Buildings sought to make dilapidated tenements safe or have them demolished; the Sanitary Committee pressured the Health Department to maintain the condition of tenements; the Policy Committee worked non-stop to suppress that gambling racket; and the Committee on Eviction and Destitution gave financial help to amilies in danger of being broken apart “and the children sent to institutions, the mother to scrubbing, and the father to a lodging house.” Mainly, however, the thrust was to teach the poor to help themselves.

On May 27, 1905 F. Norton Goddard died suddenly of a brain hemorrhage at 44 years old. The man who had made the needs of others the focus of his life and fortune was suddenly gone. Thousands marched to his simple funeral at All Souls’ Unitarian Church at 4th Avenue and 20th Street. At his request there was no eulogy. Among the mountain of floral tributes was “a huge sheaf of lilies sent by President Roosevelt,” according to The New York Times. By the end of the year the Civic Club ceased to exist.

The handsome club building stayed in the family however, until Alice Winthrop Goddard’s death in 1946. Her estate sold the building to The New York Estonian Educational Society, Inc. for $25,000. The Society still has their headquarters there. In 1992 the Society, which was founded to unify Estonians in New York, initiated a $100,000 restoration including brickwork, decorated stonework, replacement of deteriorated balustrade elements and the painting of the mansard to replicate a green copper patina. Goddard’s beautiful French clubhouse sits little-changed since 1899. It was designated a New York City Landmark in 1978.

NYEES History

The New York Estonian Educational Society was born on December 7, 1929. a meeting of the various local Estonian organizations was convened to unify the Estonians in New York. 77 members were present, and the “Unified Estonian Organization” was created. On August 7, 1930, a special meeting was convened, and a new name was created for the group: “The New York Estonian Educational Society”, in an effort to purchase a building and minimize the tax implications of a private purchase – the Society established its headquarters at 310 Lenox Avenue in Harlem.

In the fall of 1938, the Society moved to bigger quarters in Harlem at 5 East 125th Street. In 1943, Estonian Educational Society, Inc. was formed to facilitate the purchase of an appropriate property for the Society – the building at 243 East 34th Street was then purchased for $25,000.- in 1946, and the Society was able to have its Annual Meeting in its own building in1947. The influx of Estonian refugees after World War II brought many more Estonians into the Society, and the Estonian House became a very active center for Estonian activity in New York.

In 1950, the Society purchased a large piece of land in Long Island, which was subsequently developed by local Estonians – buildings, a pool and a sports facility were built, and this became the summer camp for local Estonian children.

Since then, the Society has served as the center and focal point of Estonian activity in New York.

Known as the Estonian House (Eesti Maja), the building houses a number of Estonian organizations such as the New York Estonian School (New Yorgi Eesti Kool), choruses for men and women and a folk dancing group.[3] Vaba Eesti Sõna, the largest Estonian-language newspaper in the United States is also published at the New York Estonian House. The Estonian House has become the main center of Estonian culture on the U.S. Eastern seaboard, especially amongst Estonian-Americans.

Friulians

The Famèe Furlane of N.A. Club was founded in 1929 in New York City by a group of Friulan immigrants living on the East Side of Manhattan. The area from 37th Street to 23rd Street, between 1st and 3rd Avenues was known as “Piccolo Friuli” at the time and early meetings were held at Marchi’s Restaurant on 31st

Street. The first President was Pietro De Paoli (1929-31); he was succeeded by Emilio de Piero (1931-35). Clemente Rosa became Pre-sident in 1935 and remained in office until 1976. The Civic Club on 34th Street, between 2nd and 3rd Avenue, today known as the Estonian House, served as the first official clubhouse from the mid 1930’s to the early 1940’s.

Between 1948 and 1953, the Famèe Furlane headquarters was located at the corner of 28th Street and Second Avenue. The property, owned by the Club, was soon claimed by the City of New York as the entire area underwent urban renewal. As a consequence, during the 1950’s, the Friulani were obliged to relocate to Queens, Long Island, Westchester and the distant suburbs. The members of the Famèe Furlane who had previously lived in a compact community were widely dispersed. For more than twenty years, the Club maintained an office in Jackson Heights; it continued to sponsor both annual and semiannual events at other locations. On May 6, 1976, a short time after Peter Vissat had been elected President (1976-1999), an earthquake in Gemona del Friuli sent a shock through Friulan communities throughout the world. In New York, it reawakened the Friulani’s resolve to establish a permanent “fogolâr” or meeting place. The clubhouse in College Point was inaugurated in 1980 and to this day serves as its headquarters. Marcello Filippi succeeded Peter Vissat as President in 1999. Today, the children and grandchildren of Friulan immigrants continue to kindle the hearth of the “Fogolâr”, and affirm their connection to Friulan culture and heritage.

Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Italian region: a northeast Italian region bordering Austria, Slovenia and the Adriatic Sea. It’s home to the sharp-peaked Dolomite Mountains and vineyards producing white wines. Trieste, the capital, was once part of the 19th-century Austro-Hungarian Empire. Its famous sights include the old quarter, the waterfront Piazza dell’Unità d’Italia square and Castello di Miramare, a former royal residence.