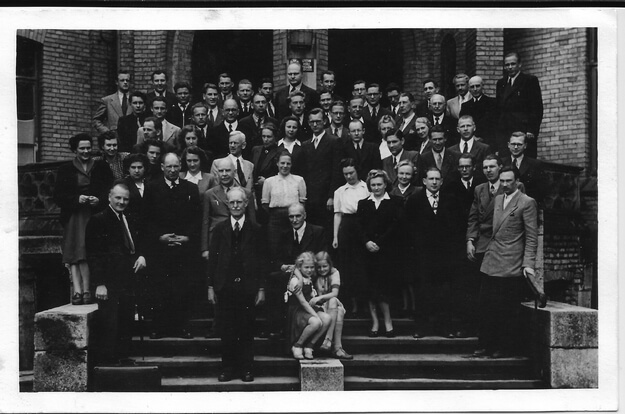

Helga Merits

The Baltic University in Hamburg, Germany, opened in March, 1946. Photo courtesy of Helga Merits

For us displaced persons, an essential part of our life is hope. Without hope, our life would be intolerable. Hope for our future, hope for a better fate of our native countries.

These were the opening lines of the Information Bulletin of the Baltic University from the 12th of July, 1947.

The Baltic University was created by academics from the three Baltic countries, all refugees, in Hamburg, Germany. Hamburg was in ruins, there was no money, no means, but there was an idea and the courage to give it form.

The university opened its doors in March, 1946 and though it all started well, very soon problems began.

Hope was an essential element to keep everybody going.

The editor of the bulletin wrote these first lines to counter rumours that had been spreading that the university would be closed down.

Though this fear was very realistic, it was not yet imminent.

The editor wrote that: “The intention of these rumours is to spoil the fine spirit of the University and to take away hope.”

But this was not exactly accurate: a rumour machine had been brought to life by a group of psychology students, hoping to contribute something to the understanding of the psychology of displaced persons.

Their scientific experiment consisted of the spreading of a rumour, looking at the speed with which it was spread and looking at the changes the message underwent.

Negative messages went fastest and without considerable changes.

Positive messages went slowly and underwent more changes, all in a negative direction.

The rumour which was believed most was that the university would close.

The Estonian psychologist Eduard Bakis worked at the Baltic University and he studied the psychology of displaced persons.

Whether he had asked for the creation of a rumour machine, is doubtful, whether he asked his students to help in his research into the mentality of DPs, very certain.

The students of the Baltic University were kept busy every day, with lectures from morning until late evening, with programmes for the weekend.

But most refugees were staying in camps, with fewer activities and more worries.

Though the morale of the DPs was at first not as bad as anticipated, regarding the traumatic experiences all had gone through, after a year apathy set it, which got worse after another year.

Though the lack of privacy in camps was an important factor which made life difficult, the feeling of being cut off from past and future also had a big impact, further compounded by being dependent upon the refugee organisations.

Eduard Bakis and his students, all refugees themselves, tried to understand what it meant to be displaced and what it meant to live for years in a camp.

The rumour of the closure of the university became a fact two years later.

Most students emigrated and continued their studies elsewhere. Eduard Bakis continued his research and came to the conclusion:

But, as the experiences and emigration have shown, there still remained an undercurrent of hope and the possibility of starting new activity.

Except for a minority (…) the personalities maintained a hidden power of recovery.