Estonia and its fellow Baltic countries joined NATO on 29 March 2004, but the story of its path into the alliance goes much further back, as Adam Rang explains in his Estonian World article. A rarely seen document shows Estonia was already working towards membership in 1949, despite the country’s occupation by the Soviet Union.

The security strategy of Estonia over the last three decades can be best summed up in three words. “Never again alone”.

Those words were uttered by former Estonian president Lennart Meri when, on his 75th birthday, the Baltic countries joined NATO on 29 March 2004.

Joining NATO was described by Estonia as “a courageous move in the interests of universal peace and as an important factor of the poster policy of the Eastern democracies in the strengthening of freedom and security in the North Atlantic area, to which the Baltic area also belongs.”

Such platitudes would hardly be a surprise 19 years ago.

Estonia had fully restored its independent state just over a decade earlier and had worked relentlessly on the democratic reforms necessary to join NATO as well as the European Union and cement itself into the Western alliance of democracies.

Except, those words weren’t penned 19 years ago.

To understand Estonia’s journey into NATO, you have to go much further back. That description of NATO actually comes from a rarely seen statement issued by Estonia 74 years ago during the founding of the alliance on 4 April 1949, the anniversary of which will be marked next week.

“Estonia is still under the illegal occupation and domination of the Soviet Union,” the statement, written by Estonian diplomat Johannes Kaiv, continues, “and is, therefore, prevented from manifesting openly its keen interest in this pact.”

Estonia’s letter on the founding of NATO, signed by Johannes Kaiv, an Estonian diplomat based in New York.

“I have the honor to offer my best wishes to the signatories of the North Atlantic Pact, and to express my confidence that they, inspired by ideals of democracy, of individual liberty, and of the rule of law, will strive relentlessly for peace with justice, which excludes peace at any price. Therefore, I express the belief that countries, which were forcibly deprived of self-government and independence will benefit by this noble endeavor,” the letter said.

Estonia’s expression of interest in NATO was formally noted, as shown in this response from the US undersecretary of state at the time, Dean Rusk, who later served as the secretary of state to US president, John F. Kennedy.

Estonia’s expression of interest in NATO was formally noted by the US undersecretary of state, Dean Rusk.

Latvia and Lithuania issued similar statements in 1949, all welcoming the creation of NATO and their belief that it would benefit the world, including nations such as theirs then under occupation.

Defined Estonia’s position

The Estonian foreign minister, Urmas Reinsalu, told Estonian World that the statement in 1949 defined Estonia’s position in Europe as the country never surrendered to the Soviet occupation.

“As Estonia celebrates 19 years in NATO, a whole generation has grown up in the safety and under the security umbrella of the alliance,” Reinsalu said.

“As Russia’s aggression in Ukraine continues and Europe faces its biggest security threat since the Second World War, I am grateful for the unity NATO and its members have shown in responding to it. But this new geopolitical situation has shown that there can be no grey zones in Europe and I hope that soon we can welcome Ukraine in the alliance.”

The story of NATO, like the story of the Baltic countries, is often told from the perspective of “great powers” with the assumption that small countries between them have little agency in the seemingly inevitable historical changes thrust upon them.

But these letters are the start of the NATO story from the perspective of the Baltic countries, which blows apart that narrative.

How were these statements possible?

Throughout their long occupation, the Baltic states remained independent in both their own domestic law and in international law.

To many around the world, this seemed largely theoretical given the grim situation on the ground. But there was one part of their states that the Soviets were unable to dismantle. The foreign ministries of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania continued to function – in exile.

Their diplomats stationed abroad continued showing up to work in countries that continued to respect the independence of the Baltic states, even though those diplomats temporarily had no legitimate governments back home to report to. The Soviets tried to convince countries that diplomatic buildings belonging to the Baltic states should be handed over to the Soviet Union, but some refused – most notably, the US, UK and Brazil.

This enabled the Baltic states to partly function independently in exile, such as by issuing passports. Most crucially, however, it provided a continued official voice for the Baltic states, educating the world that the Baltic states were still legally independent and were working to fully restore their states.

As they pointed out, the Baltic countries were forcibly and illegally annexed by the Soviet Union in 1940 as a result of its collusion with Nazi Germany to divide Europe into spheres of influence, as outlined in the secret protocol of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact.

This violation of international law led to the Second World War, sparked first by the Nazi invasion of Western Poland, but which was shortly followed by the Soviet invasion of Eastern Poland. The Baltic countries declared neutrality at its outbreak, unaware that they had already been consigned by both aggressors to Soviet invasion.

The Nazi-Soviet alliance was maintained for the first two years of the Second World War before the surprise attack ordered by Hitler on the Soviet Union. Yet, at the end of the war, the Soviet Union re-established its grip on the Baltic countries and continued its own occupation, which it justified through the staged annexation that took place by force in agreement with the Nazis.

This situation meant the Baltic states were the only members of the pre-war League of Nations not permitted (until much later) to join the post-war United Nations.

Even many of those around the world who supported the plight of the Baltic countries regarded the noble work of exiled diplomats to be a lost cause. The restoration of international law for the Baltic states looked, for a long period, like a pipedream. Yet they continued their work regardless.

For example, when NASA in 1969 requested goodwill messages from the nations of Earth to be sent to the moon onboard Apollo 11, official statements from both Estonia and Latvia were included.

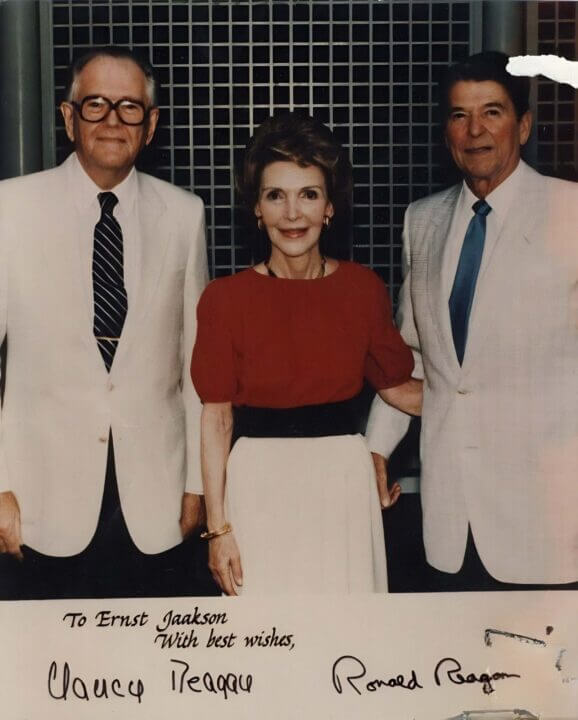

“The people of Estonia join those who hope and work for freedom and a better world,” declared Estonia’s consul general in New York, Ernst Jaakson, on behalf of Estonia.

“On behalf of the Latvian nation I salute the first men on the Moon and pray for their safe return,” said Anatols Dinbergs, then head of the Latvian diplomatic service. “May their achievement contribute to world peace and restoration of freedom to all nations.”

History vindicated them.

Jaakson and Dinbergs, for example, both appointed by their preoccupation governments were both promoted to ambassadors by their post-occupation governments.

The Baltic states did not “become independent” from the collapse of the Soviet Union, as too often described. They formally declared that their illegal annexation was null and void, and that occupation troops must leave, helping facilitate a chain reaction across other captive republics that ended the Soviet Union.

It is partly thanks to exiled diplomats the Baltic countries exist today based on their legal continuation since their founding as republics in 1918.

This means their statements in 1949 welcoming the creation of NATO and indicating the Baltic states should be members was – and still is – the official position of the Baltic states at that time.