Helga Merits

I’m sorry I never took a picture of my grandmother’s kitchen.

It was small, a cupboard on one side, showing her decorated cups and plates, and a small tin of sweets.

The sink was of granite.

My grandmother used a soap beater for dishwashing, in which every once and a while a new block of green soap was put.

She had a paraffin stove on which a pan with meat cooked all night, to make it absolutely tender.

The scullery was far bigger and always cool.

This was the place where the washing was done, the potatoes were kept and the canning jars with berries and other fruit stood.

I can close my eyes and see the kitchen, be in the kitchen, walk through it; only the smell is missing.

I never took a picture there.

When I started to realise that it is nice to have pictures of day-to-day objects, rooms, things you always use, but do not pay much attention to, it was already too late.

The house was gone.

I can still see the kitchen, but I can’t show it to others.

Photography used to be rather expensive and I’m still surprised by all the pictures I was able to find for the different films I have made.

Happily, there were some people with cameras and everyone ordered pictures, whenever there was a photograph around.

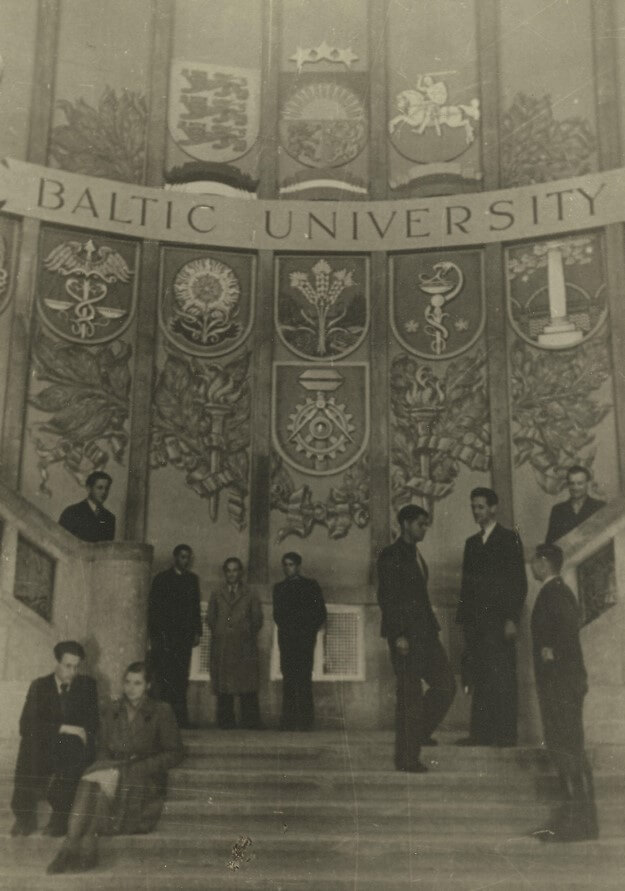

When the Baltic University was officially opened on the 14th of March 1946 and they were about to start with the first speeches, someone realised there was no photographer and no one to take a picture of this historic event.

A student was sent to fetch one; fortunately, he succeeded in time.

The result was a bunch of pictures of stiffly standing students and teachers on stairs, but nonetheless one of these pictures became an icon of the Baltic University and almost all students had this picture in their collection.

That a film even existed about the Baltic University was beyond my dreams.

Arved, an Estonian student, wrote to me one day as casually as one could: Perhaps you might be interested to learn that in the summer of 1947 my American sponsor wanted to have a 16 mm film of Pinne-berg campus.

She paid the expenses and I had professional filmmakers from Hamburg make what I believe was a 30-minute film of campus life.

Some of the professors too, but I believe I was too scared of prof Öpik to bother him.

But I am not sure. I can try to locate the film for you.

Arved did not have a bank account at the time and so the sponsor sent some cans of Maxwell House coffee, which he could sell at a high price.

The financing of the film, as Arved explained me, was the result of a black market deal, which was totally forbidden and one could get imprisoned for this and thereby lose refugee status, leaving you without any help or finances.

It was a risk, but at the same time a way of living everyone was used to, as it was the only way to get nutritious food like herrings or eggs or other necessities.

The black market was essential to everyone.

The coffee deal was done in a couple of minutes.

A crew was hired and the film was made.

It was screened once for the students, who had to pay 15 cents to be able to see themselves, but as I understood, it was well worth it: they had to laugh, seeing themselves for the first time on film.

The 16 mm film was located, 66 years after it had been made, and it was sent to Arved.

But then the message came: This is the most difficult letter to write.

The film is junk and I have already disposed of it.

It had been extensively edited.

Typewritten sections of text were added with pictures of kittens every minute to fit their taste and interpretation. (…) Please do not write me. I feel most embarrassed.

But I did write, asking him to get it out of the garbage bin and begging him to send it to me.

He did so immediately – even if to the wrong address.

But I received it after waiting for long, long days, fearing it was lost and that I would never see these images of the Baltic University.

I watched the film, over and over again, fascinated to get a glimpse of life at the university in 1947.

The editing, the childish pictures which had been put in the film, the cutting of scenes, it hardly mattered to me, as there was still so much interesting material left that I could use for my own film.

Many others saw the 1947 film after me: Jekabs, then almost ninety, recognised his mother working in the kitchen; Sarma recognised her deceased husband standing in line for food; Reinhold saw his father walking out of the university.

There will be a time when no one will recognize anyone who appears in this film any more.

But it will remain a testimony of the time when professors and students, all refugees, were studying, working and living together at the Baltic University.