Helga Merits

I miss the long letters that I received when starting my research into the Estonian refugee community.

The elderly people were willing to write or to phone, but as they lived far away and long distance calls were still expensive, writing was the best way to communicate.

Mostly four to eight pages long, the letters were in regular handwriting and always a treasure of information, news, anecdotes, and memories.

Pictures were added, newspaper clippings and copies of documents.

But with the passing of the years, I gradually received fewer and fewer letters, until the last person I was corresponding with passed away.

The lock-down, the weeks in which time seemed to stretch out, would have been a good opportunity to start corresponding with other people, to start writing proper letters instead of e-mails or short messages via WhatsApp.

But I didn’t, as there were so many other things on my mind.

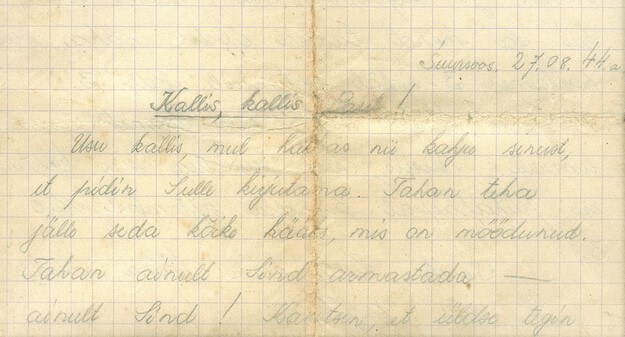

I have a letter written to my father from the end of August 1944.

One single letter, though probably there were more; from the letter I could determine there was a correspondence going on between my father and a girl, Regine.

I was surprised by the date of the letter.

By the end of August the Soviet Army was already in Estonia and the situation was chaotic.

But apparently letters were still written and received, and answered.

I wondered how the postal service worked in these very last weeks before the reoccupation of Estonia.

The letter was written on the 27th of August and in this letter Regine is asking whether they could perhaps meet: on a Sunday, 3 September, three o’ clock near the Tall Hermann tower, where they could have a view over Tallinn.

She was either trusting the postal service, or trusted someone who was delivering the letter for her, or maybe she was just hoping for the best, as there was nothing else to do.

This is a one and a half page letter and for me, reading the letter all these years later, much remains unclear.

Her letter is a response to a letter my father wrote.

Something has happened which she regrets and therefore she had to write.

She hopes he will forgive her.

There had probably been another boy, as there was one thing she wanted to make clear to him: “I only want to love you, only you.”

My father took most memories and experiences into his grave, dying far too young, leaving children too young to ask any questions.

Only some fragments of stories remained, sometimes not more than one sentence.

No stories survived about Regine, but there was a mention of a girl my father was going to meet.

The story doesn’t tell whether my father forgave her.

Neither does it say if he wrote a response saying he would be there on the third of September, or whether he guessed she would be coming to the appointment, without his confirmation.

The story does tell she never arrived, not because she didn’t want to see him, but because of a bombing, which killed her.

My father fled the country a few weeks later.

He carried the letter with him, from Estonia to Germany, to Denmark, to Holland, from eastern front, to a hospital, to a prisoner of war camp to a refugee camp.

Folded in between his identity papers, a thin yellowish paper, written in pencil was the invitation for a date that never took place.

The letters are fading, the paper is starting to crumble.

But through the writing of Regine, reading the words she wrote, there is still – even if only for a brief moment–the promise which the meeting would have entailed: a love story in the midst of a world which was falling apart.