Helga Merits

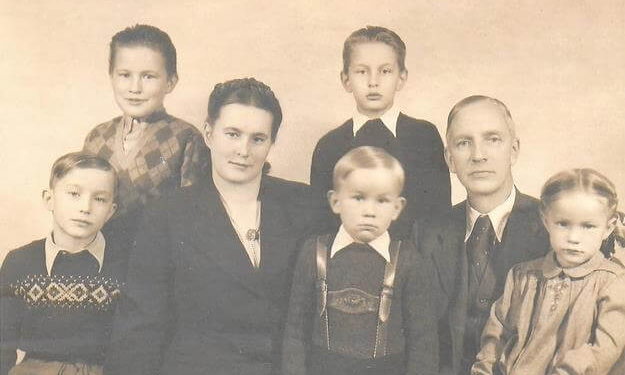

Andres’s family.

There are many stories of people that I interviewed or just spoke with, which come to my mind these days. Stories about uncertainties, about loss, about waiting and the need for being patient.

One of these is The Story of Andres, an Estonian refugee:

After the Second World War, Andres lived as a young boy with his family in Germany in the refugee camp of Geislingen.

The German economy was in ruins, its future was very much in doubt, and a return to the home country was not feasible as it was under Soviet occupation.

The refugees in Germany were strongly encouraged by their caretaker organizations to emigrate to countries that would accept them.

But what to expect in a new and unknown country? What would the future look like?

This was all unclear. When the United States opened its doors in 1948 to some 200.000 refugees to immigrate, this still seemed to many like a good option and worth the risk of taking it.

The family of Andres wanted to go, except for his father. He hesitated. He didn’t speak English and he didn’t have the skills they were looking for; he was not young anymore, what could he do in America? So they tried to find a way to live in Germany.

Life was difficult and troublesome. When the U.S. announced that between 1950 and 1952 they would accept another 200.000 refugees, Andres’s father was persuaded by his family to look again into this opportunity.

Emigrating was not easy. In addition to a visa and a sponsor, there was a lot of additional paperwork required. At the time a cartoon was published with the text: how would you like to punish a Soviet official? Let him try to emigrate to the U.S.

By the end of 1952, the family was almost there. They had completed all but the last hurdles, and they had been sent in November to the emigration processing centre in Dachau near Munich for final paperwork and health checks.

These were all completed successfully, and the very final step was a visit to the U.S. consulate where the visas would be issued.

A list of those scheduled to go there was posted on the bulletin board the day before. The family expected to be called by the end of November 1952.

But just a day or two before their names should have come up, no more lists appeared on the bulletin board.

With every passing day and no news, everyone grew more anxious and the expiration of the immigration program at year-end of 1952 came ever closer.

All kinds of rumours began to circulate. Christmas was spent at the camp without much joy.

Then suddenly a ray of hope appeared as Andres’s family and a handful of others were taken to the consulate on the last day of the year 1952.

There they sat patiently and hopefully in the waiting room all afternoon and evening.

They were told that the consulate had no more visas, but it was canvassing other consulates to see if they had any left. But as the evening hours ticked by, hope grew ever fainter. It finally evaporated completely as the clock struck midnight.

Thus ended their chance to emigrate to America. So they went back home to the refugee camp, knowing that whatever dreams they had, they needed to realize these in Germany.

And yet Andres’s dream was still to go to America. He joi-ned the Labor Service of the U.S. Army in Germany.

Andres was only 16 at the time and you had to be 18 to enlist, but he said he was 17 and 17 was almost 18, so he was accepted.

When he turned 18 there was another opportunity to emigrate to the US. He applied for a visa and was accepted.