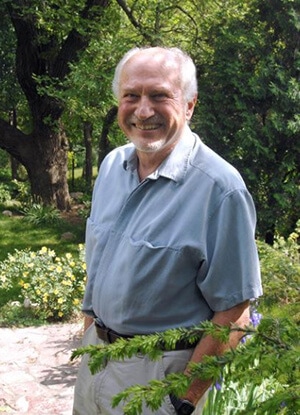

Michael Ihlenfeldt

Michael Ihlenfeldt

The Estonian Embassy in Washington currently hosts three beautiful paintings that Mr. Michael Ihlenfeldt from Peoria generously donated to the Art Museum of Estonia.

On the paintings are Natalia von Buxhoeveden, her father and her husband, though the identity of the person on the latter portrait has not been formally established.

After the stop at the Embassy the pictures will travel to Estonia to their new home in the Museum.

A retired anesthesiologist who has lived in Peoria since 1993, Ihlenfeldt inherited the painting from his mother when she died 20 years ago.

It was shipped to Peoria from her home in South Africa. Ihlenfeldt’s earliest memories of the painting were when it hung in his childhood home in Germany.

“She was my friend,” he said of the painting. “My mother said I used to have conversations with her when I was a little guy. I told her my troubles. I loved that painting. I used to wonder what she’d seen.”

Friedrich Wilhelm von Buxhoeveden

Friedrich Wilhelm von Buxhoeveden

Ihlenfeldt is a descendant of Natalia von Buxhoeveden, a member of the Estonian aristocracy and a lady in waiting to two Russian empresses − Maria Feodorovna and Elizabeth Alexeievna.

The portrait is one of three that were handed down through six generations. Ihlenfeldt also inherited a portrait of Natalie’s father, Friedrich Wilhelm von Buxhoeveden, (1750-1811) a commander in the Russian armies during the Finnish War.

“He lost a battle to Napoleon Bonaparte after drinking too much vodka — you have to include that,” said a chuckling Ihlenfeldt. That was the 1805 Battle of Austerlitz.

The commander’s portrait has been deemed a high quality copy of a Borovikovsky painting.

“It was apparently a very popular painting to copy, and the copies were very good,” said Ihlenfeldt. “They were often created by the artist’s assistants.”

“The Lady in Waiting”. Natalia von Buxhoeveden

“The Lady in Waiting”. Natalia von Buxhoeveden

The third painting inherited by Ihlenfeldt, which is of Natalie’s husband, is a low quality work by an unknown regional artist, said Ihlenfeldt.

“They think it was reproduced from a miniature,” said Ihlenfeldt.

When Ihlenfeldt inherited the portraits, he didn’t know much about them. But he knew at least one of them was valuable, a fact he learned in the early 1960s from an art restoration expert in Germany commissioned by Ihlenfeldt’s grandmother to clean the paintings.

“She impressed upon me the importance of this painting (of Natalia),” Ihlenfeldt said. “Before that I knew it was a beautiful thing, but she was the one who put it into my head that I had to be responsible and take care of it and find out who painted it. She said, “You will never know who painted it because of the Iron Curtain.”

Ihlenfeldt’s grandmother was born in Estonia. Her father was the mayor of Tallinn in the late 1800s before the family fled to Germany to escape political unrest. For most of its history, Estonia has been occupied by larger countries on either side of it. It wasn’t until the Iron Curtain fell in 1991 that Estonia regained independence from Russia.

After the fall of communism, Ihlenfeldt sent a letter to the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia, to get more information about his painting, but his query went unanswered. When his mother died, Ihlenfeldt visited Germany to bury her ashes, then took a side trip to Estonia where he learned more about his family, but no more about the painting.

Ihlenfeldt’s quest has become more important in recent years as he has gotten older − no one in his family shares his passion for the artwork and he worried about what would happen to the paintings when he died.

“I have nieces and nephews, but none of them are interested. So what do I do?”

Last year, Ihlenfeldt finally got an answer when an email to the Estonian embassy in Washington, D.C., got a quick response.

“I told them I had these paintings, and that I wanted to find out who they were of. And that I was getting old, that I needed to find a home for them — would you be intereted?” said Ihlenfeldt, who attached photographs of the paintings in the email. “There was an immediate response. They were obviously very interested.”

During the next few weeks a group of art experts in Estonia convened to look at the images. They quickly came back with an assessment — the portrait of Natalia was very special. In fact, scholars knew of its existence and had been looking for it for some time.

It’s possible that “The Lady in Waiting” is a copy, said Ihlenfeldt. The truth might, in fact, never be known. Borovikovsky was an impossibly prolific painter. Like all successful artists of that time, he had an army of assistants who painted the less important parts of the painting. They also made copies.

“It’s very difficult because there are so many Borovikovskys around, and he worked with so many painters,” said Ihlenfeldt. “It’s hard to attribute it to him. Actually, the value of the painting will be determined by the quality of the painting.”

Ihlenfeldt said the experts are telling him the quality of “The Lady in Waiting” is very good. He was told that if the painting went to auction, it could command a very high sum. But he never considered selling it. Instead, he donated it to Estonia. It’s currently hanging in the Estonian embassy in Washington, D.C., and soon will make the journey overseas, said Ihlenfeldt.

“She has traveled for 120 years on three continents — Europe, Africa and America — and it’s time to go home.”

Read the story of the paintings and of the family who had them for six generations from Peoria Journal Star by Leslie Renken, Journal Star arts reporter :